AfroCarolina Correspondence #228: Listening Between the Lines

Encountering Ancestral Grief/Rage in the Archives

This month, as a part of my Crossroads Fellowship project, Psalms by the Riverside, I’ve gone on a deep dive of Greenville and eastern North Carolina history1. Most afternoons I make my way to the Durham Main Library downtown. It’s a large, modern building that was renovated a few years ago to include four floors of books, study pods, and even a business center.

My chosen corner of the library is the North Carolina Collection Room which houses rare and out of print books, as well as local and regional archival material. My initial bristling at their strict policies around checking in and placing large bags in a locker upon arrival has recently become an acceptance of what now feels like a ritual of sorts. There’s an order to the process of arriving to this research room that grounds me, allowing me to leave behind any overwhelm at the door as I greet the librarians, place my book bag in a locker, and set up my laptop at the large rectangular table in the middle of the room.

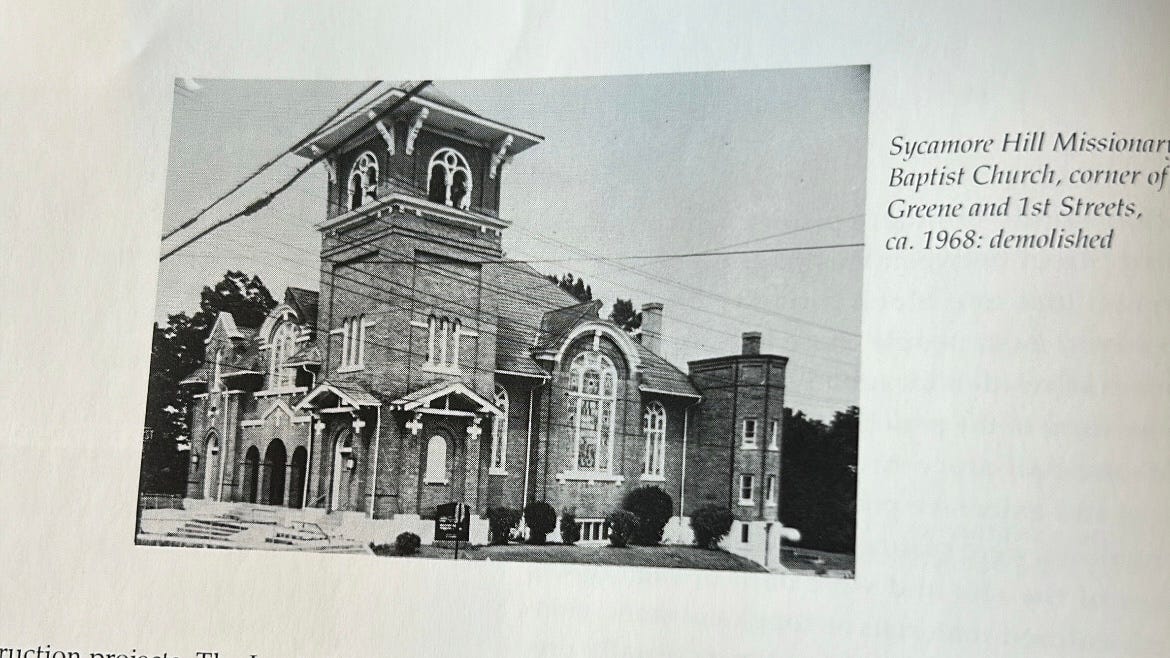

My research centers on my grandma, Ann F. Huggins’ church and the historic Black downtown Greenville community that was established in the mid 19th century and was displaced by Urban Revitalization in the 1960s. There has been little in-depth documentation around the displacement and none led by those who experienced it or their descendants. When I embarked upon this project, I knew that there would be gaps in the public histories surrounding Black Greenville and what happened to it, but I wasn’t prepared for how large (and racist) the gaps would be.

What I’m learning as a budding archivist- and my answer to the gaps in the archive, is that intuition and a connection to the spirit of blackness2 is just as important, if not more, than coming across the right documents. When I read in one book that “Prior to the [civil] war most churches had mixed white and black congregations,” this does not mean to me that Blacks and whites lived in spiritual harmony until the “divisive” impacts of the Civil War. No, my intuition, and my perspective as a Black southern woman tells me that enslaved Black people were forced to attend these white churches and receive the gospel of colonialism. Later this is confirmed when the author writes,“a group of Blacks from the white Greenville Baptist church asked for letters of dismissal and formed Hickory Hill Baptist Church.3”

Coming across this sentence I felt a sense of the accomplishment and relief the cousins, neighbors, and friends of my ancestors must have felt when they could finally, openly engage in Black spiritual community. I wondered what kitchen table conversations and whispered street corner exchanges led to their collective effort to dismiss themselves from that white church.

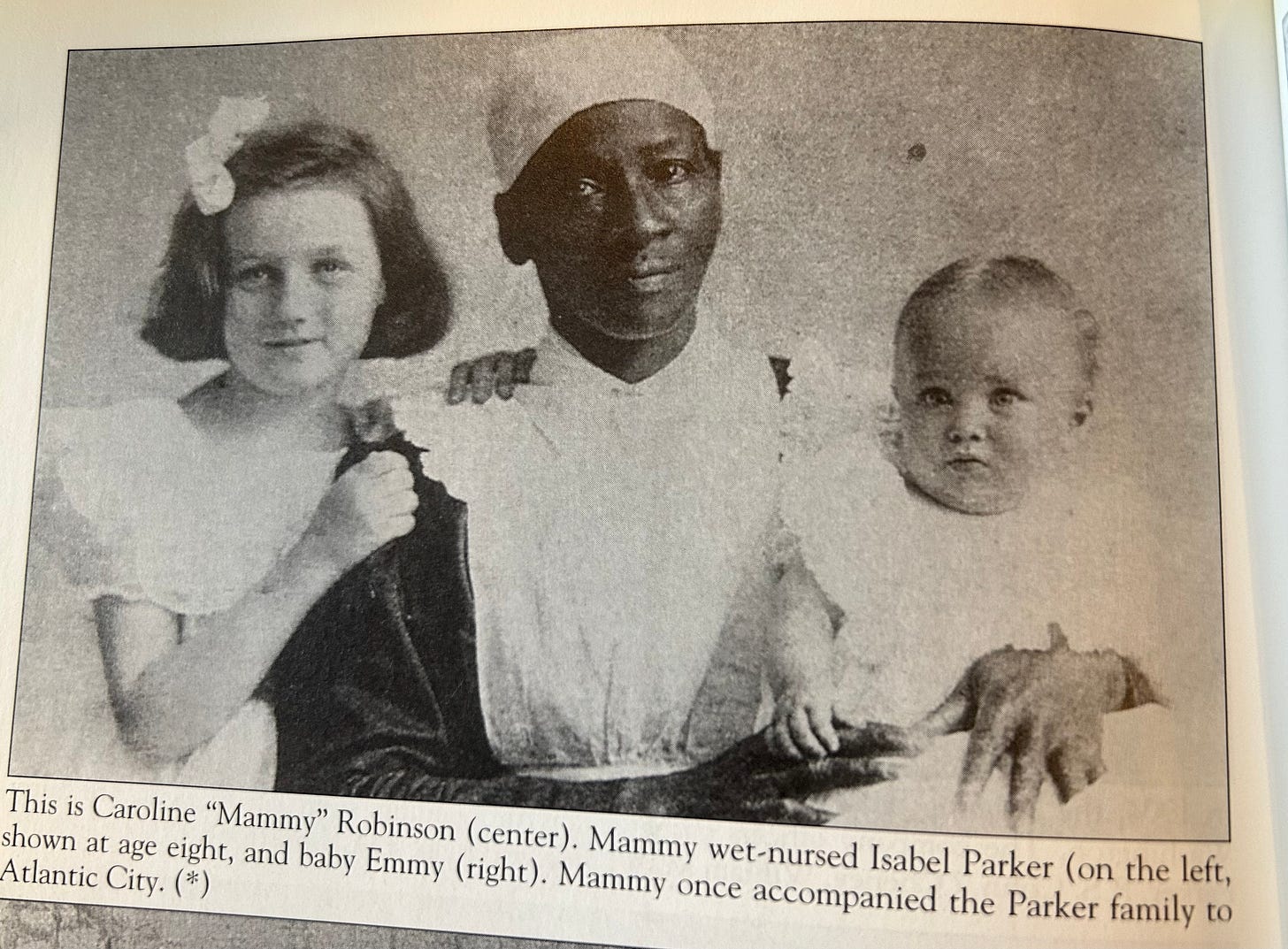

One book on the history of Beaufort County, where my Grandma Ann’s father is from, contained more photographs of Black people than the others I’d browsed combined. This provided no relief as all the Black people depicted in the 18th & 19th centuries were clearly in positions of servitude/labor and were unnamed if acknowledged at all. I felt rage rising from the base of my stomach as I turned the page to see Caroline Robinson, the only Black person whose name is recorded up to that point but is confusingly, infuriatingly ignored in the rest of the caption, with eyes full of sorrow, holding two white children.

In this work of evaluating and reconstructing public memory, I sometimes feel summoned by these Black spirits and forgotten communities shrouded in a haze of racist generalizations and misinterpretations. They implore me to hear their voices; to recognize myself in their faces and affirm them with dignity in a tongue we both know. I feel their rage too, or maybe it’s my grief/rage, knowing that there’s so much more pain, suffering, joy, magic, beauty, and blackness beyond what’s neatly printed and filed away on the third floor of the Durham Main Library.

“It is my destiny to write a praise song for every photographed elder. It is my reclamation to pull these words apart and hold them close to me and hold them far away from me in every configuration. It is my sincere intention to transubstantiate this artifact into a gift for all of our generations.” - Alexis Pauline Gumbs 4

I learned about the concept of the spirit of Blackness from Taye Amari Little. You can find their patreon here.

Architectural Heritage of Greenville Edited by Michael Cotter (1988).