Dealing with the Legacies of Racism in North Carolina

I’ve just come back from a morning walk with my grandma and her walking partner, Miss Joanne. This ritual begins at around 6:30 when one of the two women calls the other, and they discuss whether it looks like it’ll rain that morning. When they’ve decided the weather has acted in their favor, Miss Joanne, a tall, pleasant woman who lives in the house across the street, makes her way to my grandma’s yard in her floppy straw hat. Grandma Ann, in her baseball cap and black new balances, exits the house not looking back to see whether I’ve managed to rouse myself up from bed to join them. She’d already missed two days due to the weather and a few late nights.

By the time I made it outside, grandma had gone around the back of the house to retrieve her walking stick. It’s nearly as tall as she is and provides protection for the two elderly women who walk about a mile around the neighborhood staying wary of stray dogs and unkept yards. We chattered a bit, but mostly just enjoyed the stillness one can only experience in the early hours of the morning.

Now, back at the kitchen table munching on an english muffin, I’m still reflecting on the tumultuous meeting I accompanied my grandma to the other night. This year, my grandma became the first Black woman chair of the Pitt County Board of Commissioners, disrupting a 240 year old reign of good ol’ boys. One of her first accomplishments as chair was advocating for the removal of a confederate statue that had idled in front of the courthouse since before anyone could remember. The decision to remove the eyesore was made in the midst of a fiery summer filled with protests & statues tumbling down from their roosts. So of course the effort, led by Black protesters and a Black woman commissioner, caused a commotion in Pitt County.

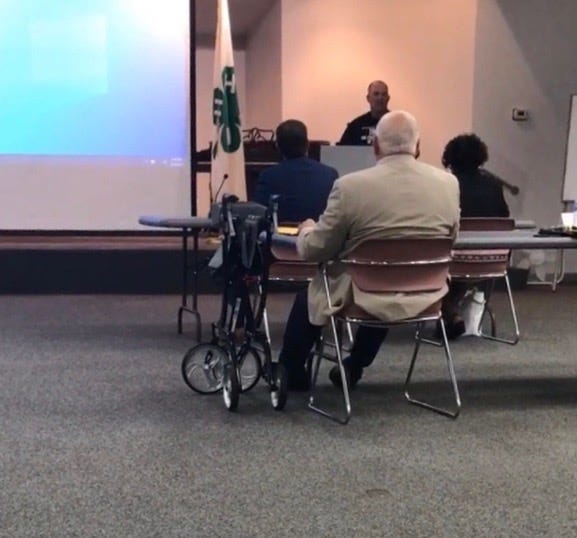

Although the statue has long since been removed, a group of white men have convinced themselves that my grandma and the other commissioners’ actions were illegal and punishable by law. So, six months later, they showed up to the county commissioner meeting on Monday evening to let their concerns be known. It was obvious who was in their crew as a few wore caps marked with the confederate flag and they spoke to each other loudly as if to warn everyone else that they came as a united front.

The meeting began with public comments so I watched as each of those white men sauntered up to the podium to make their remarks which varied between colorblind delusion and outright threats to seeking arrests, calling each commissioner by name. I watched my grandma sit there, facing those racist white men as they berated her. Her back stayed straight. She didn’t so much as turn a cheek at the slew of thinly veiled hate speech that was being directed at her.

“My saying is you catch more flies with sugar than vinegar. I feel like I don’t have to knock you over the head to present my side of it. Now if I have to, I will but I try talking.” — Ann Floyd Huggins

After each of the men exited the podium turned soapbox, a silence followed that briefly filled the room with discomfort. My body was ablaze with rage. Instead of erupting from my chair, I shot each one of those men with the fiery darts that my eyes had become as they passed by me. These weren’t faceless strangers on the internet. They were flesh and blood who could do physical harm.

I really didn’t expect to encounter racist white folks during this trip, nor did I want to write about it but I’m here to experience truth, right? While the dangers of racism aren’t confined to the south, the confidence and gaul of racists here feel more imminent. Going to that meeting reminded me of the age old battles Black people in the south are still fighting. That there are countless towns like Greenville, with groups of racist white folks doing everything they can to preserve the remnants of when we were still their property. And the numerous people like my grandma who have been living and organizing against that violence for decades.

I don’t have a positive bit to end this post on because the reality of racism in America is still very bleak. However, I am curious about the ways Black people can create deeper networks of solidarity that touch even the most isolated rural towns. Not necessarily for the sake of mobilizing mass protests like those I, and many of my comrades were involved in last summer. But to make sure that people like my grandma can feel held in accountability *and* safety when going up against the violent legacies of this country.

*This post was initially published on my former blog “Morning Glory Stories: Black Southern Resistance & History in the Carolinas” on July 21, 2021.