Interview: Behind the Scenes of the 'From Mali to Raleigh' Exhibition

Photographer, Cornell Watson and Curators, N'gamet Keïta, and Nori McDuffie discuss artistic lineage and documenting Black life through art

Tucked away in an upscale residential neighborhood just outside the Durham city limits, curators, N’gamet Keïta and Nori McDuffie, created a portal blurring the lines of time and space between North Carolina and West Africa.

This portal was named ‘From Mali to Raleigh’ and took the form of an exhibition celebrating the work of famed Malian photographer, Malick Sidibé and that of award winning, Durham photographer, Cornell Watson. It was located at Cassilhaus, an independent gallery and artist residency created by Ellen Cassilly and Frank Konhaus, from December 2024 through this past March.

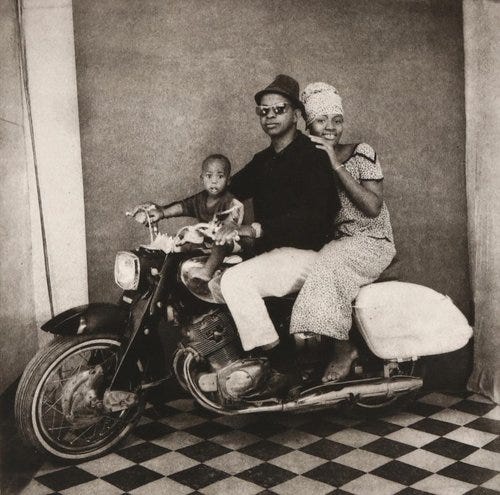

Over the months that it was housed at Cassilhaus, ‘From Mali to Raleigh’ became a gathering place for the Durham Black arts community through its robust programming which ranged from a family archiving workshop, to a motorcycle photo booth referencing Sidibé’s iconic imagery.

As the exhibition wrapped in March, it became clear that ‘From Mali to Raleigh’ needed to be remembered and archived. So this month, I sat down with Nori, N’gamet, and Cornell to discuss the context around the exhibition, their own creative journeys, and the potential of Black art.

“My mother was the first artist that I've ever encountered” - N’gamet Keïta

I would love to start with everyone talking about your artistic lineage. Who is your work in conversation with and upon whose shoulders are you standing on?

Nori McDuffie: What first comes to mind is my family, specifically my maternal family. We just have so many photo albums, and every once in a while, someone will send my grandmother a photo of when she was a kid, or one of my great grandmother. And I just think it's the sweetest thing ever. My grandmother still has all of my great aunt's clothing, pieces of jewelry, and shoes. They just do such a great job of preserving things. Being able to know your family's history just felt really cool and special to me. And I think that's part of why I do the work that I do, and who is inspiring me in that way.

I will also say I am a lover of Solange. She just creates in a way that I feel so connected to. I will also have to say Cornell, because he, too, is creating work in a way that I'm just like, that's it. The people I named serve as a blueprint- they all honor home and Black life in a particular way.

Also, Zora Neale Hurston is someone whose shoulders I'm standing on. The way she documents and preserves Black life, traditions, and language is just so powerful and inspiring. Zora lived in such a way, and did the kind work that gave someone (Alice Walker) a reason to come and collect her bones. We should all live in such a way that gives someone a reason to go and collect our bones.

N’gamet Keïta: This exhibition has been very cathartic for me. It has allowed me to open up all of my layers that represent my identity and how it's formed. So my original answer to that would be just from the media that I've consumed since childhood, but throughout this exhibition, I realized that it has been my mother this entire time. My mother was the first artist that I've ever encountered, but I hadn't seen it until now. Growing up, she always had images taken of us, like, any type of event we went to. I remember a time where we were just dropping one of her friends off at the airport and it was important for her to document that moment specifically. When we eventually immigrated to America. She brought a lot of those family albums and clothing with her. So seeing those things as a child became inspiration for my art and inspired me to document my own life. The dress that I wore for our shoot- that was my mother's dress. I felt it extremely important to kind of honor her in that way.

Yes, the mother is coming through today. What about you Cornell?

Cornell Watson: I'm definitely in conversation with Black people. That's like my prime audience. I stayed with my grandma for a lot of my grade level schooling. I’d go to her house and thumb through her photos where I’d get a glimpse of our family history. Then later on in life, when me and my partner were having kids, I wanted to continue this tradition of preserving our history through photos. It’s a lot of shoulders that I stand on like Gordon Parks and Roy DeCarava, and even folks in the journalism space like Ida B. Wells.

“We should all live in such a way that gives someone a reason to go and collect our bones.” - Nori McDuffie

Another person that’s implied with this project is Malick Sidibé. How has his work impacted your own practice and journey as artists?

N’gamet Keïta: Malick has inspired my work in a really pivotal way. Seeing him as a pioneer of photography, as an African man, or even really as an African child that had a dream; and how his community around him supported him. Which is not something that’s easy to do back home. Seeing everything that he accomplished truly inspired me in that moment to just be the artist that I always wanted to be.

Cornell Watson: Through this project I got to see Sidibé’s portfolio in a different way. The impact for me is how important documentation is. Because Sidibé’s photos are rare glimpses into a time and a place. And it defies stereotypes that people have of countries in Africa. It also makes you think about our connection, as Black Americans, to Africa and to Mali. Like, you start to see yourself in the people, in the images, and it shows just how important it is to capture these everyday moments.

Nori McDuffie: There is a lot of beauty and dignity and pride that exists within the photos that he takes. There's a sense of love and friendship, and community too. But I really love the photos. In part of the exhibition, there was a video playing in the background talking about how people were just showing up in their finest outfits, and taking their photos. I think that was like some early Instagram shit where it's just like, “Oh, I see a cute background. I look good. Let me take a picture right quick.” I don't know, maybe he started that. So I have an interest in photographing people in a studio setting, in their flyest fits where they just feel really good about themselves. Which is part of a larger story of Black people taking ownership of their own stories and their lives and feeling proud about who they are.

“The main goal was for Black people to be liberated, and these images represent that time.”- N’gamet Keïta

Cornell, your photography captures both the intimacy and collective experience of Black life in Durham. Can you talk more about how you came into this practice and why it’s important to you to have AfroCarolinians as the main subjects in your photography?

Cornell Watson: My start in photography was in my home, and then in other family members’ homes which led to expanding the definition of family. I do think about Black people in Durham in that way- like being family. If you're Black and you live in Durham, the vibe of Durham feels like a very family oriented, community-based place for Black people. I also think about how much Durham is changing and how important it is to capture what we have right now. So there is some urgency to document us right now at this moment.

The exhibition was held at Cassilhaus which is an artist residency space helmed by a white couple. What was it like bringing this Black-ass exhibit to a white space? And how do you navigate creating and curating Black art in white spaces?

Nori McDuffie: What feels most important is that we had a lot of autonomy. There are some expectations with these kinds of spaces to properly pay the folks who are curating the space, and to support Black artists- both financially, and through resources and connections. It’s also important for these art spaces to allow themselves to be shifted to make sure they’re creating a safe environment for everyone involved. Cassilhaus does have a mostly, or large white audience. So it felt like my responsibility to bring in Black folks, and curate the space in a way that really resonated with us. It became about how to make sure that Black folks can come here and take up space. We even had one of the workshops be only for Black and brown folks to be intentional about centering our people.

Cornell Watson: This experience with Cassilhaus is definitely an outlier from the industry, and I think that the reason is because it's their home and their own personal collection. They're opening it up to everyone, and they're not getting any financial gain from it. So I do think that creates some flexibility. If we were talking about a museum, I don't know if this would have been the same as far as the programming and the freedom to curate in the way that [N’gamet and Nori] wanted to curate. It's always interesting showing Black art and taking up space in white institutions.

There's a growing conversation right now in the art world of Black people. Folks like Swiss Beats and Alicia Keys who have said Black people should take more charge of our own art, and I think that's true. I also think that there's white standards around art collection, and there are things that Black artists need to interrogate a bit more. Like even in this experience, I learned a lot about fine art sales and the concept of limited edition prints and those types of things where I'm like, I don't know how I feel about making things limited to a point that only people from a certain class have access. So I think in the world of fine art, there's room to make some changes in regards to Black art.

N’gamet Keïta: What I understood throughout curating the exhibition was the need to balance the fact that it was their home and balancing how I wanted to curate the space and that can bring a lot of conversation and opinions. We definitely had a lot of autonomy in the final decision making and almost full creative control. The two most important things that I was balancing were wanting to make the space very, very Black, because there's literally nothing but Black bodies surrounding us as we're walking into this very white space, right? And also, kind of the weariness of having white people observe us to that degree. It really showed me how we all navigate things with each other based on race, and it was interesting. But I also think there is a respect that should be given because it is their home, and then also a respect that should be returned because of the sensitivity around our history.

Nori, I love that in the beginning you mentioned Solange, because now we're seeing this rise in awareness and interest around curation and multidisciplinary design, but we're not seeing many examples of what that looks like on a local or community level. From you and N’gamet’s perspective, what is the role of the Black curator, especially in a local community context?

Nori McDuffie: One of the things that was talked about in the archiving workshop was that it’s a community effort in order to document stories and then tell them. It's their mothers, their grandmothers who were keeping track of all the things that inspired Cornell to take photos, that inspired N’gamet to curate. For me, the community makes up the larger story that can be seen across time and coasts, and really across the diaspora. We get so much from our community, and I think it's important to honor the people who have built you up and who shape you.

As a curator, it just doesn't feel ethical to have your focus on the larger scene when you can't even understand how your community also needs the same thing you're looking to provide to everybody. If I have the ability, the creativity, the resources, to provide those kinds of experiences to my local community, then I should be doing that, because then there is somebody who's going to come behind me and feel inspired and take it to the next level. So I think it's paying service, it's really building a roadmap, and it's knowing that people on a local and grand scale deserve the same kind of experiences.

N’gamet Keïta: I feel like I'm just now getting into this work, but it has always been a passion for me to learn and educate myself more on Black history, and to essentially find the proof of connection for myself, first and foremost, to Black people from this land that I felt the moment that I learned about our history- about the transatlantic slave trade and African history. I immigrated here when I was eight. It was an entirely new world so I automatically gravitated to the people that I am used to and who looked like who I grew up around. So I just gravitated to Black folks for that reason here. But then, when learning about our history I was heartbroken, I was shocked. But at the same time I was like, we all the same. Like, y'all African too- we all African.

But then, as I assimilated even more into Black American culture, I started to see more of the divisiveness that is between us, and it really just set a fire in me to prove- to reaffirm my own identity and reaffirm the closeness that I felt. In learning those initial stories, however horrific, I think that was my first connection that I made. Then I started to dig deeper on how we all connect in the smallest ways. It's always been a passion for me to learn more about us and to kind of be an encyclopedia of us. I think it's just my personal life's mission, and I'll probably be doing this work until the day that I die. I feel like now I'm essentially coming into my power to really allow my voice to be heard. My role as a Black curator, is to affirm myself, and by way of affirming myself, having that confidence in sharing this knowledge to show and express to other Black folks within my community that we are very much connected. We've just been separated.

“As much as our minds might forget certain things, our bodies never do.”- N’gamet Keïta

In the exhibition you visually brought together Cornell’s and Sidibé’s work through the kente and mudcloth framed photos. Can you speak more to the connection of Black Durham of today and Sidibé’s Mali of the 60’s & 70’s?

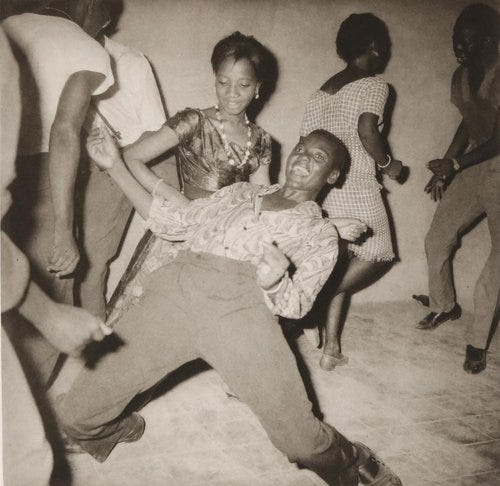

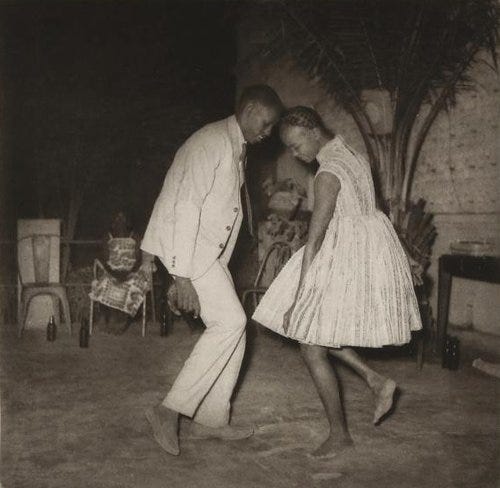

N’gamet Keïta: In the simplest way, it was the body movements and how we all collectively live joyfully in a very similar way. One of my favorite pairings is one of Watson’s [photographs] where everybody is just shakin’ ass, like with the cigarette in hand, and just throwing it back. On the opposite end is Sidibé’s image of Black folks having a good time, getting down. The connection in those two images was in the way that the bodies were positioned. It brought back some memory, some connection for me, that I was like, oh, they're doing the same thing, but not necessarily doing the same thing. I feel that as much as our minds might forget certain things, our bodies never do.

What has the reception to the exhibition been? Has anything surprised you about folks’ response to it?

Nori McDuffie: It's been received quite well. Folks have emphatically shared their excitement and appreciation of the exhibit. I think we all have a certain vision for when we're creating something, but when someone shares its impact beyond what you're imagining it's just like, in your words, Alexis, affirming that your life force is powerful. It was one of those moments where I was like, Oh, my life force is powerful. There were also a lot of young Black folks in the space, which made me happy, because I do think that there is a bit of an illusion that Black people and Black young folks don't care about art or that they don't have interest in the art scene, but they absolutely do.

N’gamet Keïta: Before I answer this question, I want to say one more thing about the last question. Behind the images, a lot of pivotal moments were happening for Black people around the world in a very liberatory way. Around the time that the civil rights movement was happening here, and subsequently Black Americans gaining their civil rights, the same thing was happening in West Africa with Black folks there gaining their independence. It's important to note that these revolutionaries were in communication with each other and were inspiring one another. The main goal was for Black people to be liberated, and these images represent that time.

As for the reception I've gotten, surprisingly, more of the feedback I’ve been getting has been from older white people at the exhibition and them being able to look at Black people enjoying themselves, and then be able to draw their own personal memories from that. I think it speaks to how manipulated we've all been in holding up white supremacy. It speaks to humanity and how some of us can see ourselves without necessarily being the ones that are in the forefront.

Cornell Watson: It was beautiful to see how many Black people showed up throughout all of the programming for Mali to Raleigh. This was definitely one of my favorite exhibitions which had a lot to do with the programming and the people. It felt like a community where I was excited to show up because my people were gonna be there and it was gonna be a good time. The way that Nori and N’gamet curated this should serve as a blueprint for future exhibitions. They activated this in a very different way that felt good and should be incorporated into future programming for other exhibitions.

I love how you all are just leading me into my questions. My last question is what is your hope for the Black Durham arts community, especially with this political moment we’re in?

Cornell Watson: I hope for more collaboration between Black people within the art space. It’s a different experience when you get to collaborate with other Black artists to create something like this. So I hope to take from this and inject it into the rest of the Durham arts scene where we can be together and take photos of each other, have conversations, and see ourselves in the art. With so much that's happening right now this felt like an escape from it for a little bit. It was a nice reprieve from it all. Not saying that all art has to be a reprieve, but being in community definitely helps insulate the mental impact of it all.

Nori McDuffie: My hope is that I can continue to go to more events that are full of Black people, full of Black young folks. And that more people get opportunities like N’gamet, Cornell, and I to show their work.

N’gamet Keïta: My hope is for Black folks to be in community where we are cultivating spaces that allow all of our experiences to be seen and heard and understood. And possibly through that, we will be able to connect even deeper than we already do. I think that can truly only be done through art and conversation. I'm not just talking about Black immigrants who come here, but even amongst ourselves here. We talk about how there are differences between a Black person from the south and a Black person from the north of America. In those separate communities there are even more individual experiences of Blackness within them. So I would love more community in conversation about ourselves to understand ourselves better.

AfroCarolina Correspondence is currently a free publication. If you enjoyed this post and would like to contribute to my work, please consider sending a tip below.

Alexis, thank you for documenting and sharing this conversation. I know the exhibit was amazing. The thoughtful questions and vivid reflections drew me in, prompting me to pause and make mental notes to consider/revisit later. Thanks, again!

Alexis, I felt like I was in the room with you for this conversation. Hearing about this very intentional presentation and cultivation of our culture was a special experience.